Share this

Travels Through Mysore

by Rose Busto on Jan 8, 2021 10:52:41 AM

What a difference a year makes! This time last year I was getting ready for my annual research trip to India. Right now, I would have been feeling the excitement that accompanies the build-up to travel and the anticipation of meeting old friends and colleagues in a far-flung location.

The purpose of these trips has always been the same- to further my research into India’s ascetic traditions and their impact on modern postural Yoga. Throughout, the highlights of my trips have involved the charismatic, colourful characters I encountered along the way.

In Chennai, I met the very engaging Head of the Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram. Sri Sridharan Laxmidharan, “Sir”, as I was advised to call him, is an investment banker turned brahmin and Yoga Therapist whose wry sense of humour was very much in evidence. When I thanked him for giving me his valuable time for an interview, he thanked me for breaking up the monotony of a tedious day of Yoga Therapy! A follower of Desikachar, Krishnamcaharya’s late son, “Sir” belongs to the same tradition as Krishnamacharya, the Nathamuni Sampradaya, and was able to offer some fascinating insights into the great Yoga master’s life and methods. Although deeply religious and devoted to rituals and prayers in his private life, he described Krishnamacharya as a “great Vedantin” who, despite being deeply traditional and conservative, a pragmatist: an innovator who “wanted to bring Yoga out of the house and to the masses”.

Most of the acaryas and brahmins I met in Mysore were also from the Nathamuni Sampradaya. Few people realise Mysore is home to a thriving industry based upon competing schools of Ashtanga Yoga. Beyond the Ashtanga Yoga Research Institute (AYRI) founded by K. Pattabhi Jois, there are several schools which do not benefit from the global interest generated by Jois’s high-profile followers. Indeed, their students are mainly drawn from the local community. Their following, however, is increasing, driven by the migration of some of the AYRI’s foreign students. Disenchanted by the institute’s perceived commercialism, limited accessibility, their devotion rocked by revelations of historic abuse, these students are devoted to their gurus and return year after year to learn from them.

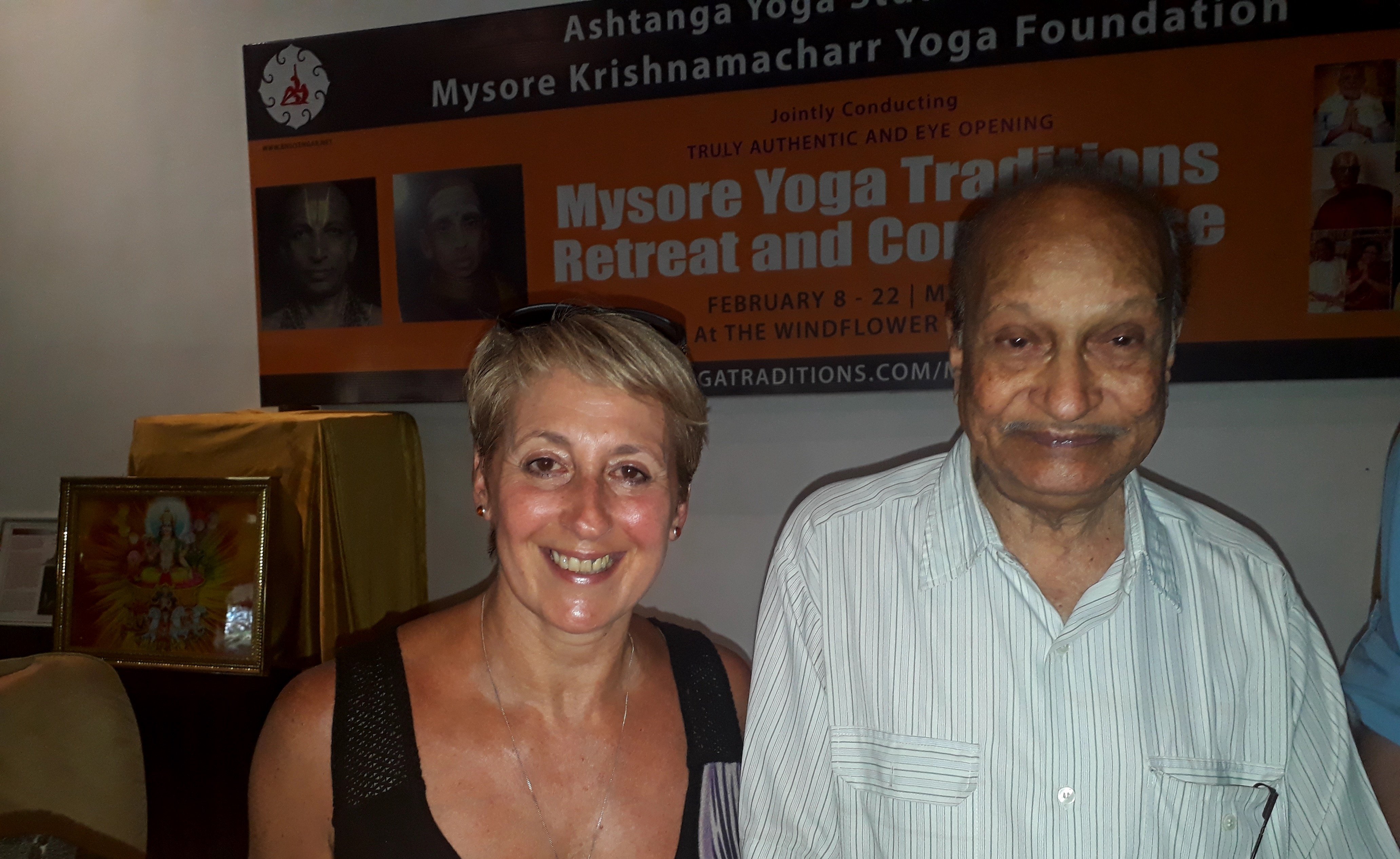

Such a guru is B.N.S. Iyegar who, while no relation to his more famous counterpart, B.K.S., is part of the same vast Iyengar clan. An energetic, if rather overweight, 94-year-old man, he is one of the few people alive who remembers Krishnamcharya. With his gap-toothed smile and limited English, he embraces a typically Indian pedagogical style which leaves no doubt as to who is the teacher and who the student. In one early-morning class, he made us move into trikonāsana at least three times, greeting each poorly executed move with shouts of “NO, NO, NO” and “Go BACK!” until he was satisfied with our entry. Unlike some of his peers, Iyengar eschews the trappings of wealth, choosing instead to live in a modest cave-like dwelling on the way to the hilltop temple of Chamundil.

Another of Krishnamacharya’s last surviving students is Dr. T.R.S Sharma. A modest, self-effacing man, he remembered Krishnamacharya jumping onto his stomach during a Yoga demonstration with no warning. As his “master” was prone to a touch of showmanship during these performances, he was surprised, but not shocked, remembering it as “great fun” at the time. An extremely articulate, highly educated man, Dr. Sharma holds a Doctorate in English and lectures at various Indian universities. A self-professed humanist who dislikes what the calls “superstition”, he nevertheless confessed himself perplexed by current Western interpretations of Yoga: “To reduce Yoga to mere gymnastic s is to show no understanding of the Indian mind”. Unfortunately, my interview with Dr. Sharma was abruptly and prematurely terminated when he espied B.N.S Iyengar: “You must excuse me- I have wanted to meet this man for a very long time!” Although my professional pride was slightly dented, the sight of these two old men, each as sharp as the other, reminiscing together, was heart-warming to behold.

From their institute in Mysore, M.A. Jayashree and Professor M.A. Narasimha teach Sanskrit and Yoga philosophy to mostly foreign students. The brother and sister, who live and teach together, collaborated with Mark Singleton on his translation of Yoga Makaranda, Krishnamacharya’s manual on Yoga and were a significant source for Mark Singleton’s research for his ground-breaking book, Yoga Bodies. Jayashree is also a renowned chant teacher. When I asked her how the brahmins of the city reacted to a woman taking on a role which was traditionally the preserve of brahmin males, her reply was: “They don’t like it, but I don’t care. “Her father and uncle, both brahmins, had taught her the scriptures from childhood and she considered herself fortunate to be able to perpetuate their legacy. As I interviewed Narasimha, it became increasingly apparent that he was disillusioned and angered by Western scholarship’s reduction of Yoga to a system of mere physical exercise, particularly given his role in facilitating the research which led to it.

Few people know that Krishnamacharya was not just a Yoga master and teacher, but a renowned Sanskrit scholar and that his first post at the Palace was as a Sanskrit teacher to the young royals. Dr. Alwar, who traces his genealogy to the Alwars, the twelve Tamil poet-saints of South India, is the Deputy Director of the Sanskrit College in Mysore. As I interviewed him, I realised that he had more knowledge of philosophical systems, East and West, than any other scholar I had ever come across, including within my own academic community. As we talked about our respective doctoral studies, I asked if I could read his thesis, which was on a topic of particular interest to me. He replied, very politely, that he would love to show it to me, but it was written in Sanskrit. With my limited knowledge of that language, it was very unlikely likely that I would have been able to understand a dense philosophical treatise, so I regretfully had to decline.

Dr. Alwar’s father, Professor Lakshmi Thathachar, is the Director of the Samskriti Foundation, an organisation which aims to preserve ancient Indian manuscripts by digitising them for posterity. Extremely fragile palm-leaf manuscripts found in Indian homes are carefully wrapped in red cloth and stored in a library. They are then digitised and catalogued. This is not as simple as it sounds. Heat and humidity take their toll on the tiny palm leaves. The worst threat of all is the appetite pf the insects who love to feast on them. Pattabhi Jois’s claim that the manuscripts on which Krishnamacharya based his system were eaten by ants is usually met with a knowing smile and a dose of cynicism by scholars. We would do well to remember that they are a very real threat and something that Western conservationists, with their temperature, light and humidity-controlled environments, don’t usually have to contend with.

The highlight of my trip was a visit to the Samskriti Foundation in Professor Thathachar’s hometown of Melkote, where I observed the conservationists ant work. To hold one of those ancient manuscripts, some no bigger than my thumb, in the palm of my hand, was a rare privilege and something I will never forget. Later, I experienced one of the most magical nights of my life. As we sat beside a sacred bathing lake after a traditional meal provided by Professor Thathachar in his own home, this stern and conservative old man visibly relaxed and softened as he regaled us with tales of the old saints and sages by the light of the moon.

I had hoped to go back to Mysore before travelling to Pune in January to meet up with my old friends, all of whom were extremely accommodating and generous with their time but, sadly, due to a certain pandemic, that was not to be. This time, however, we shall be meeting up online. The Mysore Yoga Traditions Conference, which facilitated all these meetings and interviews, will take place in January and at a fraction of what it would cost “in real life.” While we may not experience the magic of India, we will still be able to hear what the scholars and brahmins of Mysore have to say about the history of Yoga in Mysore. I, for one, will be riveted to the screen, feeling grateful for the one thing this pandemic has brought us- the ability and willingness to connect with people of different cultures and to receive, directly, the collective thoughts and wisdom accumulated by some remarkable individuals through many years of scholarship and inquiry.

If you want to be part of this unique experience, please contact rose@ultrayoga.com, and I can put you in touch with the conference organisers who will be able to register you. Alternatively, you can contact the convener, Andrew Eppler, directly at okiebaba@gmail.com

*All photo credit to Rose Busto*

Share this

- World Of Yoga (75)

- Teaching Yoga (64)

- Yoga Business & Marketing (38)

- Thinking Of Teaching (15)

- COVID-19 (6)

- Stress Awareness Month (5)

- Yoga For Men (5)

- Community (3)

- Online Presence (3)

- Pregnancy Yoga (3)

- Yoga Teacher Revolution (3)

- CPD Academy (2)

- Experience (2)

- Living The Yogic Life (2)

- Amrita (1)

- Anatomy (1)

- Asana (1)

- Discussions (1)

- Interview (1)

- Kids Yoga (1)

- Meditation (1)

- Mindset (1)

- Roots of Yoga (1)

- Standards (1)

- Traditional (1)

- Trainee (1)

- January 2026 (1)

- December 2025 (2)

- September 2025 (30)

- August 2025 (2)

- July 2025 (1)

- June 2025 (2)

- April 2025 (1)

- February 2025 (2)

- January 2025 (1)

- December 2024 (1)

- September 2024 (1)

- August 2024 (2)

- July 2024 (4)

- June 2024 (1)

- May 2024 (5)

- March 2024 (1)

- February 2024 (2)

- October 2023 (2)

- September 2023 (6)

- August 2023 (4)

- June 2023 (1)

- May 2023 (3)

- April 2023 (2)

- February 2023 (2)

- January 2023 (2)

- December 2022 (4)

- November 2022 (4)

- October 2022 (6)

- September 2022 (3)

- August 2022 (5)

- July 2022 (4)

- June 2022 (1)

- December 2021 (1)

- November 2021 (6)

- October 2021 (1)

- September 2021 (2)

- August 2021 (1)

- July 2021 (3)

- June 2021 (1)

- May 2021 (2)

- April 2021 (3)

- March 2021 (2)

- January 2021 (2)

- December 2020 (1)

- October 2020 (2)

- August 2020 (1)

- July 2020 (2)

- May 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (2)

- March 2020 (1)

- December 2019 (1)

- November 2019 (3)

- October 2019 (4)

- September 2019 (6)

- August 2019 (1)

- July 2019 (5)

- June 2019 (3)

- May 2019 (9)

- April 2019 (8)

- March 2019 (1)

- February 2019 (12)

- January 2019 (3)

- December 2018 (5)

- September 2018 (4)

- August 2018 (2)

- June 2018 (2)

- May 2018 (2)

- March 2018 (1)

- April 2017 (1)

No Comments Yet

Let us know what you think